Mutanjan: The meat-and-rice dessert loved by Indian royals

-

Published

It’s a chilly evening in the northern Indian city of Lucknow, the erstwhile seat of the Nawabs of Awadh.

We are in the courtyard of Lebua Lucknow, Saraca Estate, a 1930s estate-turned-boutique-hotel, seated around a table groaning with excess. There are flatbreads sprinkled with poppy seeds or brushed with saffron, smoky kebabs and Lucknowi biryani – a delicately flavoured dish of rice and meat cooked in sealed pots.

But the highlight of the evening, Chef Mohsin Qureshi tells us, is a dessert “you have never had before”.

What he served up next seems familiar at first.

Delicate grains of saffron-hued rice, strewn with cashews, raisins, almonds, makhana (fox nuts) and crumbs of khoya (dried milk solids), and topped with flecks of varq (silver leaf).

The scent of saffron and spices mingles with the nutty notes of cashews and almonds fried in fragrant ghee. The dish is strewn with shreds of deeply seasoned yet subtly sweetened meat.

“This is mutanjan,” Mr Qureshi beams. “There was a time when the dish was a must on a connoisseur’s table on Bakrid,” he says.

Mutanjan is now hard to find – but it’s worth finding if one can, as it defies boxes and is anything but ordinary.

The word mutanjan comes from the Perso-Arabic word Mutajjan which means to be ‘fried in a pan’. It is popularly believed that mutanjan is a dish of Middle Eastern descent. However, the genre of dishes called mutajjan in medieval Arab cookery has little in common with the sugar-laced rice-and-meat dish of the Indian subcontinent.

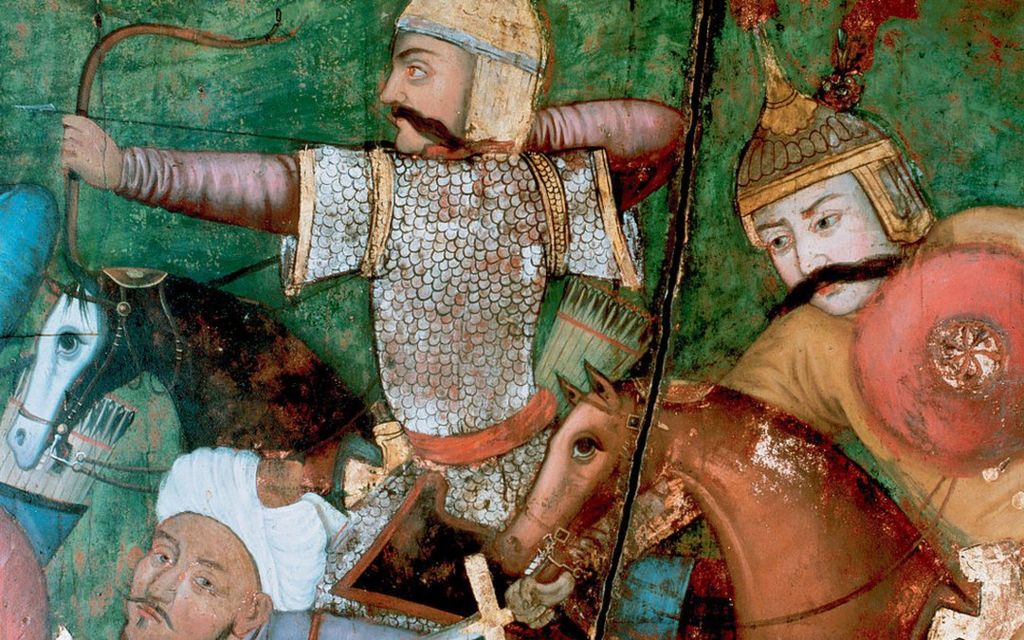

For instance, one variety is spinach fried in sesame oil and finished with garlic, cumin, dry coriander and cinnamon, while another is a dish of boiled eggs that are first fried whole and rolled in a mix of spices and salt. On the other hand, the 16th Century Persian dish called mutanjan, considered a favourite of the Safavid Shah Abbas the Great, was a braised meat stew.

In the book Qadeem Lukhn’ow Ki Akhiri Bahar, author Mirza Jafar Husain writes about 13 gifts that he believes old Lucknow bestowed on the world. Among these he named the delicate mutanjan.

Historians have also documented how food served for dinner or sent out to people from the Nawab’s house always featured mutanjan, among other delicacies.

But the dish perhaps came into the Nawab’s household from the Mughal Badshah’s royal kitchen.

Abu’l Fazl, the grand vizier of the 16th Century Mughal emperor Akbar, mentions mutanjan in his writings, among dishes served at the royal table.

Historian Salma Husain, the author of book The Mughal Feast, a “transcreation” of the 17th Century Mughal manuscript Nuskha-e-Shahjahani (Shahjahan’s Recipes), points out that it too features a recipe for mutanjan pulao from the royal kitchen of the Mughal emperor.

Earlier still, the 14th Century Arab chronicler Shihabuddin-Al Umari who described India under Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq in his book, mentioned mutanjan among dishes sold in the bazaars of India – an egalitarian street bite enjoyed by the masses, rather than a sophisticated delicacy reserved for royalty.

The mutanjan might have evolved from other dishes in the Arabic or Persian repertoire that combines sugar, rice and meat. Al-Warraq’s 10th Century book, Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchen, features a dish of rice cooked in milk along with subtly spiced chicken and finished with honey. The Indian mutanjan pulao is also evocative of the Persian Morasa Polow or jewelled rice that packs in shreds of chicken breast along with barberries, pistachio, raisins and orange peel.

Like most things in the Indian subcontinent, there is no linear narrative around the mutanjan or its origins. The dish is not only proof of the fluidity of cultural exchange but also the complex ways in which food travels and evolves. It is clear, however, that the subcontinental mutanjan pulao, albeit interlaced with numerous strands of foreign and indigenous influence, evolved over time to acquire a distinct identity in the form of a pulao.

And there’s no one way to make mutanjan or mutanjan pulao. Take for instance, the mutanjan from the princely state of Rampur in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.

Author Tarana Hussain Khan in her book Deg to Dastarkhwan describes it as a dish of sweet and savoury rice studded with sweet gulab jamun and meatballs. “The recipe calls for sugar four times the weight of rice,” she writes. Khan believes that the mutanjan was imported into Rampur’s royal kitchens via Awadhi cooks who were specially employed for this. But Rampur’s royal kitchen added its own insignia to the dish by replacing bite-sized chunks of meat with meatballs.

For Muslims of the Indian subcontinent, mutanjan is a special dish, layered with cultural memories and emotions. “In some parts of the country, particularly in the Saharanpur area of Uttar Pradesh, it was once customary to send along a massive handi of mutanjan when a new bride left her parents’ home for her husband’s,” says Husain. “A sweet and salty dish, with a hint of tang from a twist of lime, perhaps represented the mixed emotions that such an occasion evokes,” she adds.

Across the border, in neighbouring Pakistan too, “mutanjan is never a casual dessert affair – I have only seen it served at weddings, religious festivals (urs, milad) or as part of langar. It’s certainly considered a special dish”, says Pakistani food blogger Fatima Nasim. But there’s no meat in the Pakistani mutanjan, at least not in the version that’s popular nowadays.

Instead, it’s a multicoloured spectacle – a carnival on a plate. A bed of pristine white grains of syrup-soaked rice is offset by a bright pop of colours from a mix of dyed rice and comes studded with dried fruits and nuts, tutti frutti, glazed cherries and chamcham – sugary orbs of cottage cheese, in pastel hues – and crescent slivers of toasted coconut. Some versions are even finished with slices of boiled egg.

It is not easy to find a good mutanjan today. The dish is often confused with zarda (sweet, yellow rice) and other sweetened rice dishes. Luckily, a few people still make the dish. Husain, on the other hand, recommends placing an order at the Babu Shahi Bawarchi’s Bhatiyarkhana near the Old Fort in Delhi, where one Hafiz Miyan turns out fragrant pots of luscious mutanjan on request.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC: